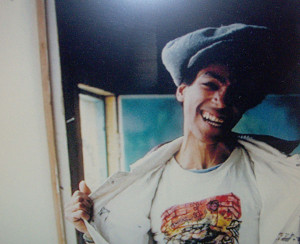

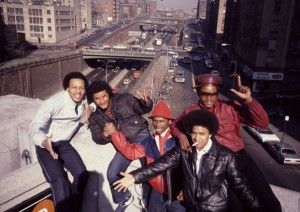

South Bronx, 1970s: A young man, circular fro, smiling, showing off his graffitied T-shirt. He’s all at once curious, precocious, hopeful and fearless. A burgeoning culture surrounds him, full of mixed influences, an environment that will either snuff out his future or propel him to greatness. This is the genesis of hip hop.

South Bronx, 1970s: A young man, circular fro, smiling, showing off his graffitied T-shirt. He’s all at once curious, precocious, hopeful and fearless. A burgeoning culture surrounds him, full of mixed influences, an environment that will either snuff out his future or propel him to greatness. This is the genesis of hip hop.

And someone took a picture.

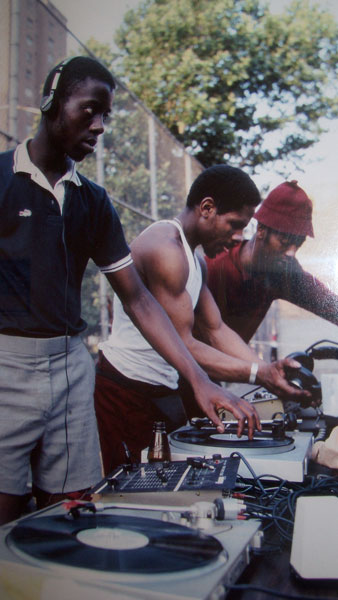

Hip hop is still young, about 30 years old by most counts, and is a culture derived from a uniquely urban blueprint. The embryonic stages of hip hop’s creative expression emerged from inner city trenches, and in some ways, came to fruition as tools of survival. It was a time before the often-named “crack epidemic,” when thundering block parties were driven by the use of improvised sound equipment; turntables and inventive scratching of vinyl records. This movement, spawned during the 1970s and 1980s in the South Bronx, became arguably the most effective grassroots model of artistic innovation in generations.

As they say, that was then and this is now, and now, this history is documented in an exhibition at the Bronx Museum of the Arts as a part of their Urban Archives series. Since today’s generation tends to look at hip hop through a hi-tech, commercialized lens, recognizing how or why the genre came to be calls for a journey back to its roots, which can only be accurately traced through its pioneers, the artists and the community activists that birthed it.

The project was envisioned by Sergio Bessa, Program Director for the Bronx Museum of the Arts. Bessa believed that in the midst of the borough’s new development, it was important to look back at its sociological history, and sought to create an exhibit that would be more inviting to members of the community largely born of that history.

The project was envisioned by Sergio Bessa, Program Director for the Bronx Museum of the Arts. Bessa believed that in the midst of the borough’s new development, it was important to look back at its sociological history, and sought to create an exhibit that would be more inviting to members of the community largely born of that history.

Bessa chose hip hop, despite the fact that he did not grow up with hip hop culture. Originally from Brazil, he discovered that hip hop was a major expository of cultural expression. Musically, hip hop was a mixture of rhythms and sounds derived from Motown, Caribbean, Latin, African and Kraftwerk. He describes Afrika Bambaataa, “Godfather” of the art form, using a mix of different rhythms that colored the roots of hip hop as a result of his Caribbean heritage. “There was the African, Latin, and soul sounds that allowed for many different cultures to participate in the genre and evolve it as well.”

Artistically, hip hop was morphing Disney and Peter Max influences into a new kind of street writing using graphics, cartoons and hieroglyphs in mural form.

Bessa felt the need to tell this story because he was discovering that many universities like Duke and Cornell have recently taken an interest in collecting the history of hip hop. “Surprisingly, no one in the Bronx was interested in doing that. There were people in the industry who wanted to get together create a hip hop museum, but I personally don’t think it’s the best way to commemorate the genre because it is constantly evolving.”

Funding for this exhibit came from the Institute of Museum and Library Services who provided a 3 year grant for the first installment of collecting the Bronx’ urban history, with the next installment showcasing the influence urban culture has had on Asian Americans. As for documenting hip hop, Bessa reflects on the year it took to put this particular exhibit on display. “We had so much fun assembling this project. In the six years I’d been with Museum, I got to know these artists and had many conversations with them about the history of genre. So when the funding came through, I knew I could just call them and they were so enthusiastic about doing this.”

For example, Bessa worked with renowned filmmaker Charles Ahearn, who began shooting short films about break dancers in downtown Manhattan and chronicles old school MCs dissecting the art of spittin’ in the barbershops, on the streets, or at home, as they reminisce about times and events “back in the day”. Images are displayed that were shot by photographer Joe Conzo, one of the first to visually document hip hop, cutting his chops on school grounds, basketball courts, and block parties. Eventually, Conzo became the official photographer of the Cold Crush Crew, the group immortalized by their early rap performances.

Graffiti in the exhibit includes shots captured by early graffiti photographers such as Henry Chalfant, who focused on artistic detail, and Martha Cooper whose work reveals the context and surroundings. Bessa also enlisted the work of Lisa Kahane, who grew up in Queens, but is best known for capturing the decay and destruction of the South Bronx in the late 1970s and 1980s.

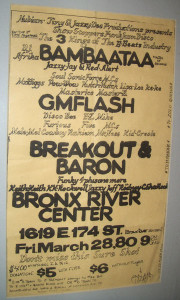

As Bessa collaborated with a host of other artists to assemble a plethora of works, the next task was to decide which pieces from various artists could properly connect the dots and tell the story. As a result, the entire exhibition is comprised of hip hop memorabilia, including clothes, photographs, and vintage rap show posters.

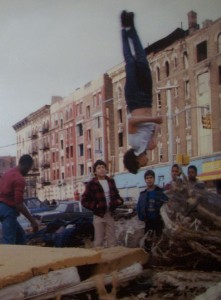

The exhibition itself is divided into two sections: “Old school” hip hop, covering its inception to the early 1990s, or “new school”, covering that next generation of Tupac, Biggie, East Coast/West Coast, iTunes, and Twitter. If you an old school head, you will remember the innocence reflected so vividly in the photos, as afros, high-tops, polyester, Members Only jackets, and the last remnants of bell bottoms pull you into a nostalgic trance. If you’re younger, or not from the region, the exhibit will act as an imaginary guide, engulfing you in the energy of the block parties, the awe-inspiring and creative acrobatics of break dancers and the camaraderie of the crews.

As you walk through the perfectly coiffed space, you see everything from a compelling piece on “How to Spell America“, to a colorful collage for ending a war. Photographs capture cool poses, people standing in their b-boy stance, rap hopefuls and girls dressed to impress at gatherings and parties. You see young men running atop graffitied subway cars in the train yards. While the Bronx was lying in ruin, burning even, you can look into the faces of these people and still see a mixture of innocence and invincibility. A display case full of random Polaroid pictures highlight faces of precocious youth frozen in time, no past or future, just a lingering curiosity about their personal stories.

Interestingly, the photographs and paintings don’t reveal gang violence, drugs or misogyny. Instead you see DJs jamming at the Patterson House Projects, the Cold Crush Crew posing as the Kings of New York, Kurtis Blow and The Fantastic Five MCs creating a new language, and the Latin and reggae musicians endlessly playing out their souls. Rap was an outcry for justice, equality, economic freedom, and community development. Rebellion was focused elsewhere, not on black on black crime, but about partying and escaping the ruins, if only for a night.

For the processed, merchandised, and packaged MTV/VH1/BET generation, it becomes more vital for this type of time capsule to exist, to recall the roots of the very culture many young people define themselves by, and often profit from. An interesting aspect of the Bronx Museum Urban Archives project is the plans to bring the program into schools, to incorporate hip hop history into the curriculum, teaching students, among other things, how to systematically collect things that relate to their own lives and identify who they are with a structured permanent archive.

There has never really been a passing of the torch in hip hop. The culture tends to be characterized by its continuous evolution from one generation to next. Each generation finds a way to redefine hip hop for themselves, borrowing from a predecessor, and putting their own spin on it, creating something new. This exhibit deftly showcases the origins of a worldwide culture, proving that, despite Rakim’s fabled rap lyric, it’s not always “where ya at,” but sometimes, it’s “where ya from”.

This Bronx Museum of the Arts exhibit ends March 1, 2010. Admission is $5.00 for adults, $3.00 for students and seniors. Members and children are free. Fridays are free.

PHOTO GALLERY FROM THE EXHIBIT:

![The Underachievers – Crescendo [VIDEO]](https://www.birthplacemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/hqdefault-2-218x150.jpg)

![Fat Joe & Remy Ma ft. The-Dream – Heartbreak [VIDEO] Fat Joe Remy Ma The Dream - Heartbreak Video](https://www.birthplacemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/fat-joe-remy-ma-218x150.jpg)

![JSWISS featuring Chandanie – LML [VIDEO] JSWISS featuring Chandanie - LML [VIDEO]](https://www.birthplacemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/JSWISS-218x150.jpg)

![Akinyemi Ends Summer With “Summers” EP Release Show [9-17-17] Akinyemi 'Summers' EP release show at Brooklyn Bazaar](https://www.birthplacemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/summers-featured-218x150.jpg)

![4th Annual NYC VS EVERYBODY Yacht Party [9/16/17] #VSYacht 4th annual NYC VS Everybody Yacht Party#VSYacht](https://www.birthplacemag.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/vsyacht-218x150.jpg)